In ‘Spinning their wheels: a reply to Jane Humphries and Benjamin Schneider’, published in Economic History Review online early view in May 2019, Robert Allen once again defends his High Wage Economy explanation of the industrial revolution in textiles. Specifically, he defends his explanation for the invention of the spinning jenny in Lancashire in the 1760s against the critique offered in Jane Humphries and Benjamin Schneiders’ 2019 Economic History Review article ‘Spinning the Industrial Revolution’. His defence turns on the productivity of hand spinners and the inducement it provided to mechanise spinning. In particular, he insists on the accuracy of his two key assumptions – that in the middle of the eighteenth century a hand spinner working full time could (1) spin one pound of yarn per day and (2) thereby earn 8d. per day. Those assumptions are mistaken.

Productivity in hand spinning was shaped by (1) the spinner’s capacity, (2) the type of fibre spun, (3) how the fibre was prepared, (4) the fineness to which it was spun, and (5) the equipment employed. It is a tall order to reduce the interaction of these variables to a single national productivity figure for hundreds of thousands of early-modern spinners whose performance is very poorly documented, if at all.

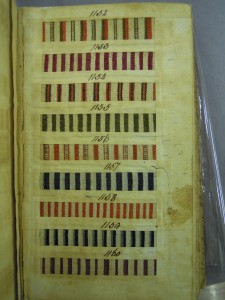

In eighteenth-century England (in contrast to many other parts of western Europe) spinners producing yarn for textiles aimed at national and international markets worked mainly under the putting-out system for a wage, determined according to piece rates. These piece rates were calibrated not simply in terms of the quantity spun (usually per pound weight), but also fineness (ie. the count of the yarn). Spinning a pound of fine 24 count yarn could often earn twice as much as spinning a pound of coarser 12 count yarn. However, spinning the finer yarn required the spinner to produce twice the length of yarn from the same weight of fibre, which demanded greater manual dexterity and took much more time. Piece rates, moreover, might, or might not, include (1) preparatory processes undertaken by the spinner, such as loosening fibre delivered in bundles, or carding it into spinable slivers prior to spinning, and (2) reeling the yarn after spinning into standard skeins or hanks for return to the employer.

Piece rates were materially and geographically inconsistent. The calculations by which yarn counts were measured differed between short-fibre carded wool (woollens), long-fibre combed wool (worsteds), linen (flax and hemp), and cotton. There were also variations between regions. Piece rates for spinning shorter fibres, such as carded wool, cotton, and flax and hemp tow, usually included the laborious preparation of the fibres by carding. The equivalent preparation processes for longer fibres – worsted combing and heckling flax or hemp – were performed by specialist workers and were not included in the spinners’ piece rate.

Piece rates for hand spinning were also (as has historically often been the case for piece rates) subject to temporary adjustments according to fluctuations in product markets, in the nature of the raw material, and in a number of other variables. The rate would remain fixed, but deductions or supplements to accommodate short-term changes in circumstances would be agreed by, or imposed on the workforce.

A piece rate defined a task. It did not necessarily specify who actually performed the work. In the case of hand spinning, predominantly undertaken by women in their own homes, the work might be performed by a single spinner, or by a number of spinners in a household, or be subcontracted out of the household. The records of the coarse linen manufactory centred at Lowther in Westmorland for 1744 are unusual in listing the number of spinning wheels against the name of each household head to whom flax was delivered for spinning. Households with more than one spinning wheel produced on average twice as much yarn as those with only one wheel, suggesting that at least two members of the household were spinning at the same time. Yet even in households with a single wheel, several members of the household might have spun on it one after another, with significant implications for output. In other households, a single spinning wheel may have been employed part of the time to spin yarn non-commercially for household use. Alternatively, it may have remained idle much of the time, as the spinner performed other kinds of work within the household. Most spinners did not spin for a ‘full time’, 12 hour day. They produced yarn only intermittently.

Different designs of spinning wheel were employed for different fibres. Wheels varied in price according to their size, the type of spindle used, and especially whether they incorporated flyer and/or treadle mechanisms, which were more expensive. Many households acquired their own wheels. Others were supplied with wheels by the local Poor Law authorities, or by philanthropic individuals and organisations. There is relatively little eighteenth-century evidence for putting-out masters supplying spinning wheels.

All this makes establishing the productivity and earnings of a ‘typical’ hand spinner working a notional ‘full time’ day a daunting exercise. It requires information about the piece rate, the definition of the task, the fibre, the time worked, the yarn count, and the spinner’s equipment and skill. Early modern sources rarely supply even fragments of that information.

So where does this leave Robert Allen’s claim that in the middle of the eighteenth century a hand spinner working full time could spin one pound of yarn per day and thereby earn 8d. per day? Is 1 lb. a day credible? Is 8d. a day credible?

The only eighteenth-century source Allen mentions for his 1 lb. a day figure derives from Frederick Morton Eden’s State of the Poor. Eden’s findings on work and wages were collected from local patrician informants, especially clergy. The 1 lb. a day figure was for April 1796 at Seend in Wiltshire, where fine, carded woollen yarn was spun. Eden’s informant reported it was ‘the utmost that can be done’ by ‘a woman, in a good state of health, and not incumbered with a family’ (Eden, iii, 796).

Schneider and Humphries quote the same source, but dismiss it as suspect. They are in good company. Julia de Lacy Mann, the doyenne of textile historians and the acknowledged expert on the West Country woollen industry, described Eden’s output figure for Seend as ‘surprising’ and ‘overstated’. (Mann, 322-3). She pointed out that during labour disputes in exactly the same area during the late 1730s, both sides agreed that a rate of 0.5 lb. a day was the maximum that could be spun by one spinner to the required standard for this type of fine, carded wool.

Mann’s judgement is supported by information Eden reports elsewhere in The State of the Poor, particularly for Worksop in Nottinghamshire, where the out-poor of the parish were provided with flax to spin into extremely coarse linen yarn (Eden, ii, 581). Few of them could spin more than 0.3 lbs per day, yet spinning coarse, heckled flax was substantially less time-consuming than spinning fine, carded wool, especially if foot-treadled flyer wheels were being used.

Eden’s informant at Seend prefaced information on spinning productivity with a long complaint about the recent introduction of spinning jennies in the Wiltshire woollen industry and the deep cuts it caused in piece rates for hand spinning. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Eden’s informant was one of those patrician opponents of mechanisation in the West Country identified by Adrian Randall in his Before the Luddites (Randall, 90, 106, 234-5) and the improbable 1 lb. a day figure a device to demonstrate the misery mechanisation inflicted on the working poor (and on the parish ratepayers who were required to subsidise their meagre earnings).

Allen insists that to understand inducements to mechanical innovation, we need output data for ‘full-time’ spinners, rather than relying on ‘vaguely defined “typical” earnings and output’. Yet he dismisses evidence from institutions – workhouses, philanthropic schemes and spinning schools – where ‘full-time’ spinning was regularly performed in the eighteenth century. He contends the evidence from these institutions is biased towards low-productivity workers.

One way to address this objection is to examine evidence from the spinning contests that proliferated in eighteenth-century England, especially for spinning combed worsted on large non-flyer and non-treadled spindle wheels. Prodigious feats of output were possible over a period of minutes or hours, encouraged by the lure of attractive prizes, but productivity declined rapidly the longer the contest lasted.

– At Sedbergh, Yorkshire in 1767, the winner was the youngest girl, who ran the whole time she spun, producing yarn at a rate that in a 12 hour day would have amounted to 5.4 lbs at worsted count 32. But the contest lasted only 17 minutes.

– At Leicester in 1785, girls aged 16 and under spun to worsted count 16. In a 12 hour day the winner would have produced 2.5 lbs, but the contest lasted only 4 hours.

– At Skipton, Yorkshire in 1785, young women spun for 12 hours. The winner produced 1.6 lbs to worsted count 21, which was described as ‘extraordinary instance of exertion in the art of spinning’.

If the competition-winning level of productivity for spinning pre-combed long-staple worsted fibre for 12 hours at Skipton was so ‘extraordinary’ that it was widely reported in the press, it is hard to believe that an everyday, ‘full-time’ spinner of short-staple wool or cotton, who had to card the fibre as well as spin it on a non-flyer, non-treadled wheel, could have produced anything close to a pound a day.

We can perhaps get nearer to the output of a typical ‘full-time’ spinner if we acknowledge Robert Allen’s objection to evidence from institutions where spinning was conducted on a full-time basis and focus our attention on the best performing spinners in those institutions. Again the evidence is for spinning worsted yarn on a spindle wheel.

– At Catherine Cappe’s spinning school at York in the 1790s, eligibility for the top reward for worsted spinners required an output of 0.75 lbs per day sustained for 6 months, at a fairly coarse worsted count 16. At the other end of the productivity scale, the minimum acceptable output was set at 0.25 lbs per day.

– at Ely workhouse in the 1730s, the top quartile of spinners produced 0.3 lbs per day at worsted count 24, a relatively high count which, according to the Northampton Mercury in 1789, was ‘esteemed good spinning in the schools’.

– at Forehoe Hundred House of Industry in Norfolk in the early 1800s, the best spinners, aged between 12 and 20, produced 0.42 lbs per day at worsted count 20 (https://virtualworkhouse.carleton.edu/scripto/transcribe/3589/4679#transcription).

For worsted yarn, therefore, we might conclude that, for modelling purposes at least, 0.5 lbs per day might be a reasonable output estimate for Allen’s notional ‘full-time’ spinner of worsted, spinning to about 20 worsted count. The weight processed would be more for lower counts and less for higher counts. This estimate would be roughly consistent with the observations made by Arthur Young on his 1780 Irish tour of the time taken to spin worsted yarns in Munster to the counts required for Ireland’s substantial yarn export trade to Norwich for relatively fine worsted camlets. In some cases Young distinguished between full-time and part-time working. His observations indicate a typical 0.5 lbs per full-time day for worsted yarn. This is also broadly consistent with the output estimates offered in Humphries and Schneider’s Table 5 for their category wool, which includes worsted.

This 0.5 lbs per ‘full-time’ day estimate cannot be extended to short-staple fibres such as cotton, where the piece rate included preparation of the fibre by carding as well as spinning it. Unfortunately, there appears to be no surviving direct evidence for productivity in eighteenth-century hand cotton spinning in Lancashire, where the spinning jenny was invented. However, we do have near-contemporary evidence for hand spinners’ productivity across different fibres in Thomas Jefferson’s spinning experiments on his Virginia plantations (in Jefferson’s ‘Farm Book’, online at http://www.masshist.org/thomasjeffersonpapers/farm/).

A precursor of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s scientific management, Jefferson required his experienced enslaved female spinners to undertake a series of timed trials spinning different fibres, in order to establish ‘what may be spun daily’. His notes on these trials are not dated, but the context appears to be his deciding in 1812-14 whether or not to acquire a spinning jenny. We can assume the women were obliged to spin diligently because they were enslaved. Allen’s ‘Reply’ dismisses this evidence as mere projections (footnote 26), but Jefferson was the quintessential Enlightenment man. He trialled, compared and recorded everything, from spinning to vegetables to the weather. Jefferson provides a useful contemporary estimate of maximum daily hand spinning productivity under coerced, trial conditions. It may only be an estimate, but, given Jefferson’s systematic practice in this and other aspects of his scientific and economic investigations, it deserves serious consideration.

The enslaved spinners were producing very coarse yarns from hemp, carded sheep’s wool and cotton for slave clothing and bedding, and doing so under duress. For linen yarn the average output per day was 1.2 lbs, for carded, short-staple woollen yarn 0.9 lbs, and for cotton yarn 0.5 lbs. It was only in spinning linen yarn, spun from hemp fibre (which is coarser and quicker to spin than most flax), that output exceed the pound a day Allen presents as standard across fibres. For cotton, the daily output was dramatically lower. Productivity in hand cotton spinning emerges as very low compared with the spinning of other fibres, including wool which also required carding. This is consistent with the opinion of experienced modern hand spinners who spin a variety of fibres. Some of the reasons are discussed in A.F. Barker, et al., Textiles (New York, 1919), 110-11. Spinners of cotton in Lancashire were free workers producing commercial yarns largely on an outwork basis at much higher (and therefore more time-consuming) yarn counts than Jefferson’s enslaved spinners. It is improbable they could have regularly achieved anything close to an output of 1 lb. per day.

Nevertheless, Allen insists at the start of part 2 of his ‘Reply’ that his pound-a-day productivity figure applies as much to cotton as to other fibres, pointing out (correctly) that Humphries and Schneider fail to offer relevant evidence about cotton spinning. He proceeds to construct a convoluted justification using nineteenth-century sources, specifically retrospective estimates for the mid-18th century offered by Richard Guest in his 1823 Compendious History of the Cotton Manufacture (which greatly over-estimated the time and cost of carding) and studies of hand spinning productivity collected by the US Commissioner of Labor at the end of the 19th century (when raw cottons and hand spinning wheels were very different from those used in the mid-eighteenth century).

Allen uses Guest’s and the Commissioner’s data to confirm his 1 lb. per day full-time cotton spinning rate for yarn spun to cotton count 13, but does so only by separating off and ignoring the pre-spinning processes, primarily carding, which also (at least according to Allen’s interpretation of Guest’s and the Commissioner’s data) needed a day to process 1 lb. of fibre.

Allen offers no justification for disaggregating spinning and carding in this way. The lack of explanation is unacceptable, because to disaggregate the two is to misrepresent the way spinning was costed by manufacturers and workers alike in early-modern England. Those Lancashire cotton putting-out manufacturers who put out work directly to spinners for a wage supplied raw cotton uncarded, expecting the spinner to undertake both carding and spinning as part of the standard task for which she was paid at a single piece rate per lb. The same was also the case for short-staple wool and flax/hemp tow, which were spun much more extensively than cotton. The observations of earnings and output for both cotton and short-staple wool recorded in the Humphries-Schneider data were all made on this basis. So too was the pound-a-day estimate from Seend in Wiltshire that Allen himself quotes earlier in his ‘Reply’. So too were several of the output estimates in Craig Muldrew’s ‘Ancient distaff’ article, which Allen has previously used as evidence for a rise in spinning wages from the seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth centuries.

So it is not surprising that Allen’s output per day for ‘spinning’ cotton ‘full-time’ appears so much higher than that offered by Humphries and Schneider. Allen’s output per day is not the notional output per day for which spinners were contracted and paid, but the fraction of it which involved sitting at a spinning wheel, which Allen calculates according to Guest’s (misleading) estimates. Using Allen’s own figures, ‘full-time’ output per day doing the work for which hand cotton spinners were actually paid (ie. carding + spinning) was less than 0.5 lbs per day.

Yet even 0.5 lbs per day is probably an exaggeration for the mid-eighteenth century. Oddly, Allen ignores the figures provided by the US Commissioner of Labor for hand spinning 12 count cotton yarn (ie. not very different in fineness from 13 count) in 1896. The Commissioner’s productivity rate for hand spinning (ie. carding + spinning) a 12 count yarn was 2.6 full-time days per pound, or 0.4 lbs per day. And this was at a date when American hand spinners benefitted from a century of selective breeding of upland cotton for its spinning qualities and the availability of improved hand spinning wheels, particularly those incorporating accelerating spinning wheel heads based on Amos Miner’s patents, which dramatically increased the productivity of non-flyer wheels spinning short fibres.

Where does this leave the High Wage Economy as an inducement to mechanisation?

Labour costs for cotton spinning in Lancashire rose substantially in the century prior to the invention of the spinning jenny. As Allen points out, referencing my ‘Fibres, yarns and the invention of the spinning jenny’ posted previously on this website (http://spinning-wheel.org/2018/06/fibres-yarns-and-the-invention-of-the-spinning-jenny/), piece rates for spinning (ie. carding + spinning) cotton in Lancashire increased between the 1680s and the 1760s, albeit from a low base. At 0.4 lbs per day, a ‘full-time’ Lancashire cotton spinner in the 1680s producing a 12 count yarn (which would have been a very high count for the period) would have earned 3.6d. per day, excluding short-term adjustments. A ‘full-time’ spinner in the 1760s producing a 12 count yarn (which would have been a relatively low count for the period) would have earned 6d. per day. At 0.4 lbs per day, 24 count yarn would have earned 12d. per day in the 1760s, but in practice the weight spun per day would have been considerably less at 24 count than at 12 count. Nevertheless, in Lancashire, at least, some spinners may well have earned 8d. per day in the 1760s. This would be consistent with the information Arthur Young received at Manchester and reported in his Six Month Tour through the North of England of 1771 of typical spinning earnings from 4d. to 10d. a day (assuming a six-day week).

Pressure on Lancashire spinning labour costs during the middle decades of the eighteenth century was a significant inducement to mechanical innovation in cotton spinning, as I argue in ‘Fibres, yarns and the invention of the spinning jenny’. Humphries and Schneider disagree. They have recently re-iterated their insistence that ‘Allen’s claim for high wages in spinning cannot be supported by the contemporary evidence’, because spinning ‘wages did not rise precipitously in the middle of the 18th century’ (https://ehsthelongrun.net/2019/05/29/spinning-the-industrial-revolution/). Yet Humphries and Schneider provide no information about precisely which fibres, dates and locations they are referring to, nor about how they conceive the relationship between piece rates and ‘wages’.

Between the 1680s and the 1760s, piece rates for spinning cotton in Lancashire increased by two-thirds. That may not have been precipitous, but it was certainly substantial, and it was in cotton spinning that the key mechanical innovations emerged in the 1760s. The flaw in Allen’s wage-induced innovation explantion for those inventions lies in evidence that pressure on spinning costs in mid-eighteenth century Lancashire (and adjacent parts of Yorkshire) was not confined to cotton. It extended to the region’s larger worsted industry, and probably to the region’s linen and woollen industries as well, yet it did not trigger mechanical spinning inventions in those industries. What may have been a necessary condition for innovation was not a sufficient one.

The increase in spinning piece rates in Lancashire was the product of a specific regional context. It was not matched elsewhere in England. As Julia Mann points out, spinning piece rates in Wiltshire for short-staple, carded woollens appear to have changed little between the 1710s and the 1760s (Mann, 324). The substantial growth in cotton spinner’s piece rates in Lancashire does not prove there was a national High Wage Economy for spinners. 8d. for a ‘full-time’ day was not a norm across all fibres and all regions. Indeed, as Arthur Young reported in his Six Month Tour, in Staffordshire and the East Riding of Yorkshire, less than a hundred miles from Lancashire, there were places where there was no paid manufacturing work for women and children (see this website, Gallery: Spinning with Arthur Young). They experienced not a High Wage Economy, but a No Wage Economy.

Regional variations in spinners’ earnings were not confined to England. They can also be observed in France. Cotton spinners’ earnings in Normandy, eighteenth-century France’s counterpart to Lancashire for cotton manufacturing, appear to have been markedly higher than those of spinners of other fibres elsewhere in France. Arthur Young, in his Travels during the Years 1787, 1788, and 1789, recorded information he was given about spinning earnings as he travelled across France. He averaged them out at 9 sous per day, a figure used by Allen in his article ‘The Industrial Revolution in Miniature’ to demonstrate that spinning wages were lower in France than in Lancashire. But Young’s 9 sous per day was his averaging of all his observations of spinning earnings across France, i.e. spinning of flax, hemp, cotton, coarse wool, and fine wool, in many different regions of a country more than twice the size of Great Britain.

According to Young’s informants, as I pointed out in a previous blogpost, earnings in Normandy for spinning cotton were considerably higher than 9 sous a day. Country spinners near Le Havre earned 16 sous per day, at Yvetot in the Caux 12 sous per day, at Rouen, described by Young as ‘the Manchester of France’, 12 sous per day, while good cotton spinners at La Roche-Guyon, on the edge of the Normandy cotton spinning zone to the south-east, earned 12 sous to 15 sous per day. The 12 sous to 16 sous per day Young recorded in Normandy represented 6d. to 8d. a day in English money. That is the mid-range of the 4d. to 10d. a day Young had previously recorded for cotton spinning at Manchester. In other words, if hand spinners in Lancashire benefited from a High Wage Economy, then so too did those in Normandy. Yet high earnings in Normandy failed to induce mechanical innovation in spinning and the jenny enjoyed limited success there.

Of course Allen’s argument for relative factor prices as inducements to technical innovation rests not only on the price of labour, but also on the cost of capital. Capital costs were, Allen argues, higher in France than in England. Yet even if that were the case, it seems unlikely the cost of capital in France would have inhibited innovation in the way Allen suggests, because the capital cost of a domestic jenny was so much less than he thinks. Allen assumes a new 24 spindle jenny cost 70 shillings (‘Industrial Revolution in miniature’, 908, 916). The jennies bought by the overseers at Worsley in Lancashire in the 1770s to be installed in paupers’ houses cost only 34 shillings and 36 shillings. The Lancastrian industrial spy John Holker reported that a jenny with 25 to 30 spindles cost no more than twenty ordinary spinning wheels (which in Lancashire cost 2 shillings each). If so, the Worsley jennies may well have been 24 spindle machines, but at half the capital cost Allen imagines.

If the capital cost of a spinning jenny was half the sum claimed by Robert Allen and if Normandy’s hand cotton spinners earned wages similar to their equivalents in Lancashire, then it is difficult to have any confidence in Allen’s high wage explanation for why the Industrial Revolution in textiles was British.

Bibliography of recent works.

Allen, R. C., The British industrial revolution in global perspective (Cambridge, 2009), chapter 8, ‘Cotton’.

Allen, R. C., ‘The industrial revolution in miniature: the spinning jenny in Britain, France, and India’, Journal of Economic History, 69 (2009), 901–27.

Allen, R.C., ‘Spinning their wheels: a reply to Jane Humphries and Benjamin Schneider’, Economic History Review, online early view (2019).

Humphries, J. and Schneider, B., ‘Spinning the industrial revolution’, Economic History Review, 72 (2019), 126–55.

Mann, J. de L., The Cloth Industry in the West of England from 1640 to 1880 (Oxford, 1971).

Muldrew, C., ‘“Th’ancient Distaff” and “Whirling Spindle”: measuring the contribution of spinning to household earnings and the national economy in England, 1550–1770’, Economic History Review, 65 (2012), 498–526.

Randall, A., Before the Luddites: Custom, Community and Machinery in the English Woollen Industry, 1776-1809 (Cambridge, 1991).